Other Dutch lawyers proclaimed me to be a “Specialist Dutch Nationality Lawyer”, a kind recognition of what I love to do these days. Some people know I used to print and issue passports for the Dutch government, got trained the old-fashioned way in the Dutch nationality law, etc. Over time I got to help others with their queries and supported not-for-profit interest groups and organisations. And now that I work as a lawyer for myself people rarely ask me why I am motivated to do this work, help others. If they do, I usually refer to the injustice of it all and my own values and sense of morality. It is true!

However, this week some news from Japan, a client’s case, and a question by a close friend made me look back at myself and reconsider that there may be more to it. Over the years my knowledge on the subject evolved as I did more research. Now I know more than I did in the 90’s when working for the government. Yes, I have children and a larger family with different nationalities resident in different EU and non-EU countries, yes I can be called an ervaringsdeskundige (literally experience-expert, a hands-on expert/practitioner) as some Dutch immigration lawyers refer to me, but I now realise how much my son motivated me to get here.

Today reading again the challenges (dual national) families in Japan are experiencing (see below). I just saw in a bit of self awareness how it all links together for me. I may at times repress part of my own history because it is not always easy to think about. It’s a difficult story to tell, but maybe sharing this will help others, maybe it will stop repeats. Maybe it will show someone not to give up hope. I still haven’t.

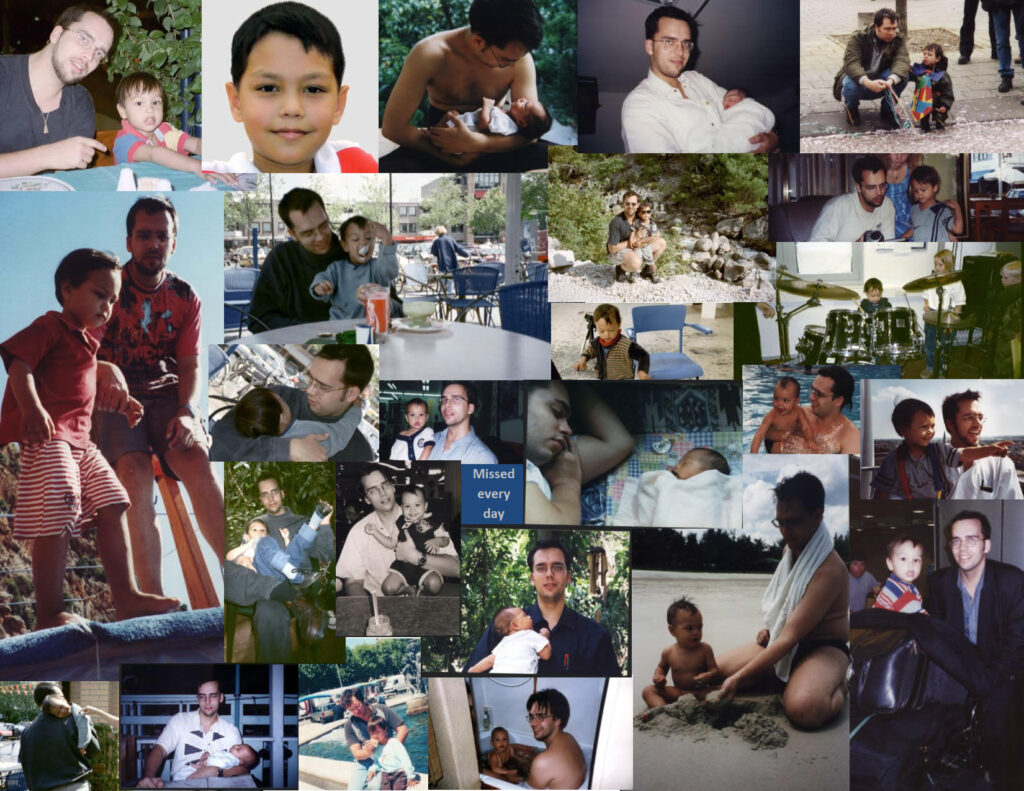

So let’s open up with my very personal story. In 1994 I met a Thai journalist whom I married in 1997. Our son was born in 1998 when I was working as consular officer at the Dutch embassy in Bangkok. The marriage unfortunately didn’t work out and in 2000 when my son was 2 years old, we divorced. At which time my ex wanted to focus on her career and willingly gave me sole custody. I was a single dad from that day on. Not easy, but happily. When my work changed and circumstances forced us to move to the Netherlands, I offered my ex opportunities to join, which she declined. She did come for a holiday but again chose her career. Without discussing this with me she must have regretted her decisions because 3 years later, in an elaborate international scheme, she took my son away. In 2003 while we were in the US my then 5-year-old son was taken away without my permission.

I returned to the Netherlands and immediately went to the police to ask for help locating and returning my son. Until then I only had some hearsay of what transpired and the US authorities were unwilling to assist. My son was located with the help of the Dutch branch of Interpol and Thai police, he was in good health. However, I was immediately told that they could do nothing further. I was referred to the Dutch ministry of justice who were very understanding and trying to assist. They took my case and formally submitted a request for the return of my son. The Thai ministry of justice declined.

Through my ex and her lawyer, I was told that if I would go to Thailand I would be imprisoned. As a former consular officer who previously helped and visited Dutch nationals in prison, I recognised the real risk of this. However, I was offered the alternative and would be given unlimited phone calls and was told that over the next few months we would need to sort things out. The Dutch justice department wrote me, and then told me when I phoned them, that they could do nothing more. I just had to accept the offer of calls and try to work things out between ourselves.

Initially there were weekly phone calls. Then after a little while I was told it wasn’t always practically possible. I was bordering suicidal, traumatised, had periods with PTSD, but just knowing my son was alive kept me going. Over time my 5, 6, 7… year old son withdrew himself from our bond. He became less responsive, less happy to talk to me, and when he was about 10 he showed me a bit indirectly he didn’t appreciate the contact and calls. Birthday presents I sent by mail did apparently arrive but my ex was happy to point out that more expensive presents were welcomed. Calls over the years reduced to a yearly happy birthday call and by about 16 just messages. I didn’t, and don’t, know what he really thinks. If he feels abandoned by me, angry, sad, oblivious or just doesn’t know what to think. I have no idea what his mother told him about me and worried because the signs of a parents’ influence were there. I have always let him know I miss him and love him no matter what, I hope he realises that and doesn’t think it is just cheap talk.

My son is now 24 years old and I almost never get a response to a message or question. A read-receipt sign of life is now about all. I have always hoped that when he would be a teenager, or became an adult (Dutch law 18 / Thai law 20) he would want to know more about his father. A hope that some form of renewed contact would rekindle our father-son relationship. Even in a limited form, anything. Unfortunately, this has not happened to date. I know he is alive and has an interest in motor bikes, but from the few things I do observe I also worry about his mental state and happiness. He seems to live the life of a disillusioned teenager, in a dark mood. I myself still have emotional scars from the traumatic circumstances of how he was taken away from me. How will this have influenced his life so far? It is not just the parent who gets hurt, children are direct or indirect victims as well.

In 1982 Thailand signed the 1980 Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction. It wasn’t until three decades later in 2013 that it implemented the necessary tools in Thai law for the treaty, and welfare of the child to be respected. Too late for us. Sometimes I wonder if I should have just gone and take him unobserved, cross a border at night… but I didn’t…

I understand my ex’s actions, I don’t want to blame her. But understanding doesn’t mean it was right how it all went. She will likely have other ideas about our history and see it differently, justifying things for herself. Maybe I indeed need to look at myself as well and some of my actions leading up to this. But even if so, I have never wanted to deny her access to our son, have always encouraged to find solutions. This was legally an abduction. And it emotionally felt that way as well, my whole world collapsed.

I now realise that this background motivates me to help people. And as my son is in this situation at serious risk of losing his Dutch nationality due to the so called 10-/13-Year Clock I would love nothing more than that the Dutch law modernises and people stop becoming victim of 19th century attitudes.

Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction

The 1980 Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction is an excellent treaty. It doesn’t just return the child back home, it is not about one or the other parent but considers the child’s best interests. It will then allow any parent to bring any conflict into a legal/court setting near the child’s usual home. Where hopefully the child’s best interest is considered. We have to appreciate that some countries can have a specific and different cultural approach rather than really looking at what’s best for the child. And even if, the opinions on what’s best for a child may differ. However, when a country signs a convention it takes on a commitment. If then local laws are not changed to reflect these treaties and conventions then it is as good as paying lip service to the rights of the child and parents. Don’t sign if you don’t implement I would say. It took Thailand three decades. The one thing even my worst enemy seems to agree with is that I am an excellent father. My son’s life may have looked very different, happy and positive I would think, if local laws married up with the convention.

Dutch nationality and passport law.

My son was thus abducted from his sole guardian parent. While I was still hopeful he would return to me, I tried to ask for a new passport for my son. I was just told, no. Not possible, only if my son is with me in person, then a passport can be issued. What if I can’t go collect him myself, how can he travel back to me? We would both have to go to the embassy. Nothing ever happened to need to follow up on this, but it was evident that it was going to be practically all very difficult. Although Dutch passport law has since changed it still does not consider these kinds of situations enough.

Now my son is 23 and in 5 years he is at risk of losing his Dutch nationality through the so-called Dutch 10-/13-Year Clock. The government has no qualms to take the nationality away from children like my son and has so far not changed this nationality law which creates the possibility of automatic loss. The fact that this Dutch young man was abducted and the circumstances will have no bearing on this. The law states he is now an adult and he should get a new Dutch passport himself. I am not allowed to be involved with that anymore. Fair enough, he is an adult. But he is still young enough not to appreciate all the ramifications.

And with the loss of his nationality there will be another barrier between me and my son and a possible future change in our relationship. Ignoring myself, the loss of nationality would also lose him many other rights, his birth rights. And how would he perceive this? Maybe he feels abandoned by me. I frankly don’t know, but if he does, he may feel abandoned by a whole country. In my line of work, I often see the emotional scars this leaves on people. Nationality is part of their identity. Even if they never considered this before. Even if they were 1st, 2nd or 3rd generations, it does feel totally wrong if it is not your own conscious choice.

This week, for the fist time, I learned that Dutch politicians are questioning the method of automatic loss. The EU Court of Justice verdict on Tjebbes created these considerate political questions. I am glad to say that not only will a real positive change stop me from getting many future clients, I myself will then feel a big emotional relieve. Although there is also a lot of opposition in the Netherlands against modernising the law I have a glimmer of hope!

What I can’t accept is that today there are still parents and children who become victims of similar situations as my own about 20 years ago. And while the Japanese stories from parents are painful to me it is also something I like to do something about. By sharing my story, and by looking at Japanese law. What else can I do to help Japan with this?

This text in Japanese / このテキストは日本語です

Historic and Cultural Background on Divorce in Japan

As with any other country, Japan’s historic cultural values are to an extend often still reflected in its current laws. Culture is custom and customs became law.

Custom / Culture

Upon marriage one of the spouses, mostly the woman, would join into the household of the other spouse. Then when there was a divorce it was the person who earlier moved into the household who would need to move out. The original family/household would normally accept the returnee and support her, or him. The couple’s child(ren) often stayed at the marital household under the custody of the remaining parent and his/her family. This is were they were born and raised and this was seen as the responsible household.

Looking back at Japan’s pre-industrial era we see that traditionally a man could divorce a woman with just a short note. Women didn’t have that luxury and could often only escape marriage by going for example into a convent. Many men did divorce and the divorce rates were traditionally quite high. Society and the state, or government, would rarely venture into the private matters of marriage and divorce. Certainly not for the masses.

The household in which the couple lived during marriage was as much about family as it was about economics. Children were not only there to ensure the familial heritage but also to secure the household’s economic future, benefiting the whole household. To date there can legally be only sole custody upon divorce which is linked to the household.

Law and modernisation

A year after the enactment of the new Meiji Civil Code the divorce rates started to decline. This drop in divorces lasted until 1963/64. The reasons are attributed to seeing the household, and thus marriage, as part of society. A strong household benefited the whole community. However, since the 1960’s divorce rates have been on the increase as now individual happiness is reportedly more of an accepted consideration. Since WW2 Japan saw changes towards individualism and women’s rights. As the political and societal ideology, which previously controlled people, was weakened, material affluence through economic development became dominant and greatly influenced the Japanese ways of life.

However, even though we see these aspects of modernisation, attitudes towards children in marriage, or upon divorce, have largely remained the same. Traditionally a divorce, where it came to the child, was a full divorce with the head of the household keeping sole custody. Shared custody is in a historical sense new to Japan. The woman regarded as the nurturing parent has seen little change, but her rights to independence have.

State – hands off!

Both public sentiment and the state’s own approach is that divorce is a private matter for the household where the state should not be involved. There is no need for big brother to come into the private affairs of a household (or two) where it comes to these private matters. This also means that parents know it is up to them to sort things out.

Taking custody into your own hands

Let’s go with the presumption that both parents love and care for their children. The traditional and current approach to the child and divorce is that there can only be one parent/household for that child. However, now in modern times we had somewhat stepped away from leaving the child in the marital household. Preindustrial households with multiple generations and members are not common anymore. Now, parents may consider each other as a competitive factor for sole custody. As the laws don’t give proper protections for shared custody parents may consider, “first come is first served”. Thus, take your child or otherwise you can loose access/custody yourself. In divorces the couple has often fallen out and may not always consider the other parent objectively or fairly. And objectively looking at what is right and best for the child is a difficult exercise, especially when the culture, attitudes and laws haven’t changed much. This results that these days you see both men and women taking sole custody into their own hands.

Court and mediation

While Japan does have its courts, and forms of mediation, where it comes to divorce there hasn’t been much change yet. We may see more and more judges looking at the child’s best interest in some proceedings. However, also there the cultural and historic view and attitudes, of a single household/single guardianship giving the best stability to the child, results in little to little or no visitation rights etc.

Foreigners and Divorce in Japan

Like many countries, Japan may still see foreigners as second rate, temporary guests. This is reflected in so many aspects of life in Japan. However, there have also been positive changes and a modernisation in this. Where it comes to divorce this may not always be reflected as such. Overcoming the idea that a foreigner is not there for the long term for the child, merely a guest in the country, feeds into the preconception and cultural background of the child being better of with the Japanese parent.

Divorce in Japan today

Many Japanese parents struggle with the same issues where it comes to divorce as foreigners do. They too are often victim of parent-kidnapped children. For foreigners this can become even more challenging. When a few years ago I came across the case of Vincent Vichot I followed this with a sad interest. Unfortunately Vincent is now on a hunger strike as he sees no other recourse.

Japan is still modernising

While we whole heartedly agree with the preference for the state and authorities not to involve too much into civil matters, where these can’t be resolved in a beneficial manner for the child, and fair manner to both parents, the authorities and courts should not just look away and ignore the plights. Don’t let parents and children suffer. EU letter to Japanese minister of justice (Japanese/English). Japan has signed a number of treaties, conventions, and doing so Japan does recognise a change to modernisation. However, it will need to then also act on this and that may first require a cultural change.

What could parents in Japan do!?

Stay being vocal, diplomatic but insistent. Don’t give up hope. Don’t give up. Don’t be send away. There is always hope. And take good care of yourself because your child would (later) not understand if you did not. Survive to be there for your child, if not today, if not tomorrow, one day. And for everyone, don’t do to others what you don’t want to have done to yourself.

What can Japan do!?

Make shared custody available in law

The cultural legal approach to separation and divorce needs to step away from the concept of sole custody. The emotional bond of a child with both parents during its lifetime needs to be recognised and protected. This affects the wellbeing of a child. The emotional bond a parent has with the child should also be respected. Only where there are extreme situations reflecting real abuse, not just accusations, or the inability to care, should authorities or a court consider sole custody, or reduced interaction. The Japanese Civil Code needs to expand the possibility of joint custody, currently only limited to during marriage. Joint custody after separation or divorce must be legislated for.

Improve on visitation rights

When stepping away from the limitation of sole custody, any visitation rights decisions should preferably be agreed upon by both parents (respecting the state non-interference culture) but can be challenged by either parent or the child. Where the deciding authority considers such a challenge it should consider, in accordance with the conventions and modern psychological/health research, that the child normally benefits from access to both parents. While mediation and soft conflict resolution methodologies are welcomed ultimately a court must review any conflict where the child or one of the parents states that no satisfactory resolution could be found.

Japanese law is lacking legislation which guides how visitation rights can be considered, reviewed, awarded and respected. Although more Japanese judges seem to grant more visitation rights to the non-custodial parent, there is still a lack of proportionate time frames (i.e. how long the child spends with both parents) and overnight stays. The premise of 60/40 should always be strived for unless, the parents otherwise agree, or this is practically not possible for the parents, or contrary to the best interest of the child.

Consider the impacts of adoption first

Currently the Japanese law allows a new spouse of the parent with custody to adopt the child. While this can benefit the new family unit and relationships, this should not be done without permission of both biological parents and a Japanese authority or court considering the best interest of the child. Also children who are capable to understand the situation and can express their wishes should be heard by any authority or the court.

Change civil registration system

Japan should review its use of its traditional civil family registry system, household registration (Koseki). Without too much of a change this could become similar to the Dutch family registration cards in use until 1939 or it’s modern civil registry system today, or the current Thai household registration book (Tabien Baan). Stepping away from the traditional family registry to a household/residency registry where custody arrangements don’t have to impede on the system. Practically the current laws do not allow a foreign spouse to be registered as head of the family (Hittousya) in the “Koseki” and upon divorce a foreign spouse cannot have its own entry. Nor can a non-Japanese parent be registered on the same “Koseki” that holds their children’s information, even where they have sole custody.

Provide cultural and legal training

Cultural approach to nationality and rights should be reviewed and officials and courts should be trained to step away from the current approach of regarding foreign parents as less deserving. Both parents created the child, both bear responsibility for the child throughout its life, and both should be awarded equal rights where appropriate. Currently a foreign spouse does not enjoy the same status as a Japanese national where it comes to the possibility to obtain custody over a child. This is totally contrary to the conventions Japan signed up to.

Recognise that parental abduction is another type of… abduction

Removal of a child by one parent away from the other parent without their permission should be seen by all authorities as abduction. Police authorities should be given clear guidelines on this, as they will want to determine at the police station to treat a case as a crime or private matter. When abduction occurs, domestically or internationally, police authorities need to be empowered to quickly return children to their usual domicile unless they fear for the safety or health of the child. This needs to be legislated for in Japan’s national laws in line with the conventions. The parent abductor should not be immediately seen as a criminal and punished or incarcerated, unless there is an immediate threat to the wellbeing of the child or others. Police authorities should refer conflicting parents to relevant support organisations, authorities, the legal system/courts. Child welfare authorities should only be contacted where there is an objective perceived risk to the child. In order to resolve any conflicts authorities should be allowed to temporarily stop the child from being moved domestically or internationally. Authorities or court should be involved immediately to consider any conflicting travel or moving plans and resolve this within a short timeframe.

Empower courts

Courts should be empowered to enforce judgements. Japanese civil law currently has difficulties with enforcing judgments even if there is a clear win by one side. Judges have little powers to sanction or imprison a party for contempt of cour and there is no mechanism for the police to assist the court in these matters.

Award immigration status or nationality status to parents.

Immigration and naturalisation laws should positively consider the continued, or new stay, of a parent of a child resident in Japan. Either on a temporary visitor status or on a permanent resident basis. Quick access to citizenship for spouses or parents of Japanese nationals should be made possible.

Equal access for foreigners

Sufficient social, health and welfare services must be made available to foreign children and spouses, or former spouses, of Japanese nationals.

Allow dual nationality

Dual nationality of a child, or spouse, or former spouse, of a Japanese national must be made possible throughout the child’s life, also as an adult. This is currently too restrictive (Japanese nationality act). Dual nationality/citizenship of a child should not result in lesser rights with respect to a foreign parent.

Convention on the Rights of the Child

Japan: signed 1990, ratified 1994

Article 3

- In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.

- States Parties undertake to ensure the child such protection and care as is necessary for his or her well-being, taking into account the rights and duties of his or her parents, legal guardians, or other individuals legally responsible for him or her, and, to this end, shall take all appropriate legislative and administrative measures.

Article 5

States Parties shall respect the responsibilities, rights and duties of parents or, where applicable, the members of the extended family or community as provided for by local custom, legal guardians or other persons legally responsible for the child, to provide, in a manner consistent with the evolving capacities of the child, appropriate direction and guidance in the exercise by the child of the rights recognized in the present Convention.

Article 7

- The child shall be registered immediately after birth and shall have the right from birth to a name, the right to acquire a nationality and. as far as possible, the right to know and be cared for by his or her parents.

Article 8

1. States Parties undertake to respect the right of the child to preserve his or her identity, including nationality, name and family relations as recognized by law without unlawful interference.

Article 9

1. States Parties shall ensure that a child shall not be separated from his or her parents against their will, except when competent authorities subject to judicial review determine, in accordance with applicable law and procedures, that such separation is necessary for the best interests of the child. Such determination may be necessary in a particular case such as one involving abuse or neglect of the child by the parents, or one where the parents are living separately and a decision must be made as to the child’s place of residence.

2. In any proceedings pursuant to paragraph 1 of the present article, all interested parties shall be given an opportunity to participate in the proceedings and make their views known.

3. States Parties shall respect the right of the child who is separated from one or both parents to maintain personal relations and direct contact with both parents on a regular basis, except if it is contrary to the child’s best interests.

Article 10

- In accordance with the obligation of States Parties under article 9, paragraph 1, applications by a child or his or her parents to enter or leave a State Party for the purpose of family reunification shall be dealt with by States Parties in a positive, humane and expeditious manner. States Parties shall further ensure that the submission of such a request shall entail no adverse consequences for the applicants and for the members of their family.

- A child whose parents reside in different States shall have the right to maintain on a regular basis, save in exceptional circumstances personal relations and direct contacts with both parents. Towards that end and in accordance with the obligation of States Parties under article 9, paragraph 1, States Parties shall respect the right of the child and his or her parents to leave any country, including their own, and to enter their own country. The right to leave any country shall be subject only to such restrictions as are prescribed by law and which are necessary to protect the national security, public order (ordre public), public health or morals or the rights and freedoms of others and are consistent with the other rights recognized in the present Convention.

Article 11

- States Parties shall take measures to combat the illicit transfer and non-return of children abroad.

- To this end, States Parties shall promote the conclusion of bilateral or multilateral agreements or accession to existing agreements.

NOTE

Please note that many/most cases in Japan relate to domestic abductions and thus the 1980 “Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction” does not apply to those domestic cases, including if a foreign ‘resident’ parent is involved. However, the principles on shared custody and what is best for the child within the treaty are universal. Once the treaty is really implemented in local Japanese law this will benefit domestic abduction cases as well.

All parents want to be treated fairly and evenly, all healthy children want both parents. And where a divorce is due to abuse and violence towards one parent, or a child, that is where a court can order appropriate protection measures. Until a court needs to intervene as such, balanced family relationships after divorce creates more balanced and happy children and thus stronger future citizens.

Kris, 18 July 2021